Many publishers boasted about flex hours and telecommuting options while the market was hot. If you telecommute to your job, you better watch out also. You've essentially become a freelancer who still collects a salary, but however good your phone or video conferencing skills, not being there in person every day makes you easier to let go. It's counter intuitive, since telecommuting employees are less expensive to maintain (no office space) than in-house employees, but when times get tough, managers want to see their employees with their noses to the LCD, and ideally working plenty of free overtime. When it comes down to it, no matter how productive you are at home, your boss will always be suspicious that you aren't putting in a full week. And a company can fire offsite employees simply by turning off their e-mail account and telling them over the phone, without that awkward cleaning out of the desk, a security escort to the door and the ceremonial handing over of the key card.

But there is a difference between the telecommuting employee and the self employed freelancer. The telecommuting employee qualifies for unemployment and the ability to extend certain benefits, including insurances. Unemployment benefits may last six months to nine months or longer, depending on the political will against passing extensions. And six or nine months of income is a lot more than most freelancers keep in an old pickle jar under the bed. One of the joys of self publishing is being your own boss, being self employed. But it comes with a responsibility, particularly for those of us in our middle age or nearing retirement age, whether we plan to stop working or not. Self publishers must be responsible for their own financial well being, and there isn't going to be any bailout for the self employed.

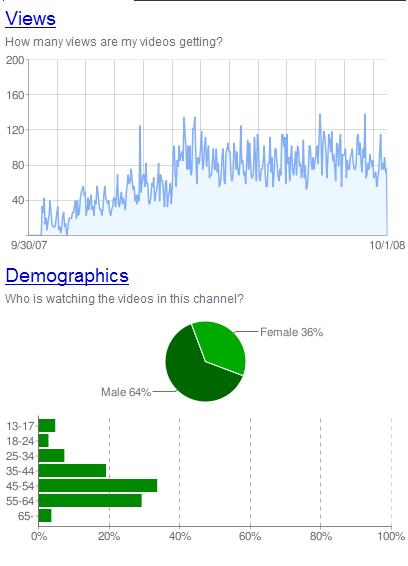

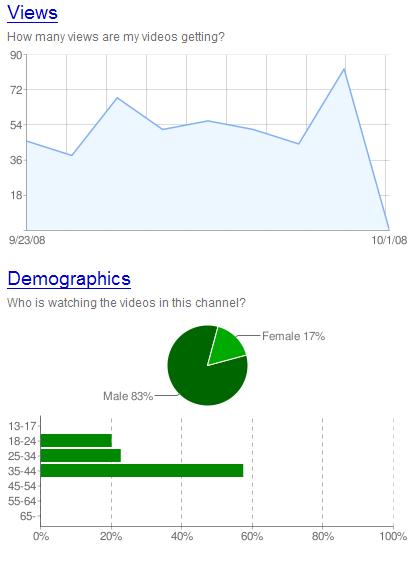

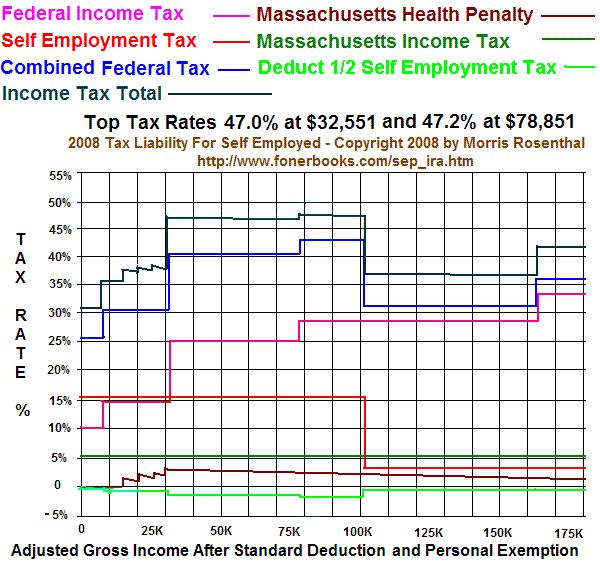

I frequently try to talk finance with the successful publishers I know, but I generally get a limited picture of their contingency plans for the future. Hopefully that's due to a reticence to talk money with a relative stranger, but I worry that many are simply living from year to year, as if they had a salaried job. (If you're living month to month, or day to day, you aren't successful yet in business, even if the path feels right). I'm particularly taken by the lack of interest most publishers show in discussing tax issues. It could be that they're using accountants and don't really understand the relationship between taxes and self employment, it could be that modern software has changed taxes into a mindless "fill in the blanks" exercise that leaves no impression, or it could be that they don't file taxes and hope that the government will leave them alone. So I'm embedding a condensed version of a graphic showing the tax rate for self employed from an article I'm writing about taxes and retirement savings.

Most of the self employed individuals I talk to in all fields don't realize that the maximum tax rate is paid by those with an adjusted gross income between about $32,000and $102,000 a year. In Massachusetts, where I live, the recent legislation to try to force the population into HMO's (major medical insurance is prohibited from sale in Mass) changes the tax system from mildly progressive to regressive, with the poor schmo who comes in just over $32,000 after the standard deduction and personal exemption paying a higher percentage than somebody making $10K or $20K more due to the health care penalty. The only thing self employed individuals can do to lower their tax rate (other than spending money in the business and showing less profit) is to put a percentage of their income into a tax deferred retirement account. It boggles my mind that some individuals buy health insurance and save nothing for retirement or food for a rainy day, as if this is a responsible position to take as a member of society. Note also that health insurance is not a deductible business expense for self employed individuals in the US.

If you want to survive as a self employed entrepreneur, whether in the publishing business or any other business, your first goal should be to live and conduct your business debt free. I've heard of some very successful entrepreneurs who built their business on a credit card, but I'm not one of them and I can't believe the statistics are in their favor. Your second goal should be to save enough money for any emergencies that may come up, from a drop in sales, to a lawsuit, from health problems to writers block. Unless you can convince Social Security to give you disability payments for running out of creative juice, you don't want to be in a situation where you'll need to get a job as a supermarket bagger if things go badly for a couple months. I worked more minimum wage jobs as a young man than I care to remember, and I don't remember any of them being conducive to creative work when I got home at night. Now that I think of it, most of those jobs required working at night, so it's not surprising.

We all know somebody who complains about their financial condition, and adds how hard it is to keep up with the car payments (on their $50,000 car). We all face different challenges in life, and nobody expects somebody in their twenties or a young parents in their thirties to have it all worked out. But at some point in your life, you either start saving for the future or you can acknowledge that you're one slip away from needing a bailout or giving up your business and going back to working for the man. It would be nice if there were a lobby for the self employed to represent the inequities we face in the tax code, but the only organizations I've come across appear to be fronts for selling - you guessed it - health insurance:-) If I don't get going on a new book this year, maybe I'll start my own lobby for self employed folks.