A simple example would be my collection of computer titles. Since I use Lightning Source to do my printing on demand, and since color POD is still too expensive for producing books with reasonable cover prices, I chose from the inception to write books that didn't require photographic illustrations. That may sound simple, but I can assure you that books related to computer hardware have always been published with heavy photo illustration. In some instances, like a step-by-step book for building PCs, those photographs are very useful, but more often than not they are filler to bulk up the page count for a higher cover price. So back in 2003, I developed an approach for troubleshooting computer hardware based on black and white flowcharts, and I even turned the lack of photographs into a selling point in the promotional book video I wrote about a few months ago.

A more general example is simply writing lean books. Trade publishers love bulking up books to achieve wider spines for shelf visibility (thicker paper stock is also common for low page count books) and the perception of higher value which allows higher cover prices. More subtle reasons include the perception of higher value for competitive purposes, and the belief that bulk equates with quality, especially in nonfiction and reference type titles. After all, if the reader is simply overwhelmed by the amount of material in the book, they are more likely to blame themselves for failing to understand the subject than to blame to author for failing to explain it. For trade publishers ordering large offset runs, the incremental page count has limited impact on the final cost of the book, the more important cost is performing the editorial and production process on the larger number of pages. When you're writing for self publication, especially if you are using print on demand, the printing cost rises far more rapidly than your ability to raise the cover price while keeping the book competitive with similar titles.

As a self publisher, you have 100% control over what you write, and that includes the ability to make changes during the editorial process. I can't tell you how many self publishers I've corresponded with who were planning to follow my print on demand model, but who changed to short run offset at the last minute because they couldn't leave out a beautiful color photograph that they referred to in the text or an accompanying DVD of photographs, audio or video. My advice to make a minor edit in the text and leave out the spoiler falls on deaf ears. Authors who have never written or published a book become married to the notion that the "something extra", the color, the DVD, the odd shaped book, adds value that will make their book sell. In my experience, the "something extra" wouldn't help sales even at the same price point, much less when it doubles the cost to the customer.

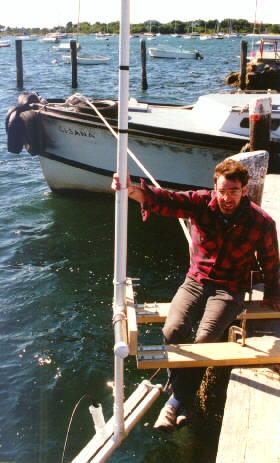

Unless your publishing business is supported by a trust fund, it's also important to write books for which you can produce all of the content. I spoke about photographs above, and while I don't use them in my own publishing business, I took thousands of photographs and published over two hundred in some books as a trade author. When the publisher asked me to provide photographic illustrations for the first trade book I wrote, I borrowed a 35mm camera, read a couple books about lighting, and learned to take photographs that were good enough to do the job. If I had hired a professional photographer, my earnings from that first book would likely have been negative, and I never would have tried a book that required a hundreds of photographs. The same is true for illustrations. I've included cartoons in a couple books, one for a trade publisher and one for self publication, relying on family members to produce finished drawings from my stick figures. Every expense you incur in preparing your book for print raises the bar for how many copies you need to sell to break even. It's easy to dream up art work and other add-ons that would make your book more attractive, but my advice is always to save them for the next edition.

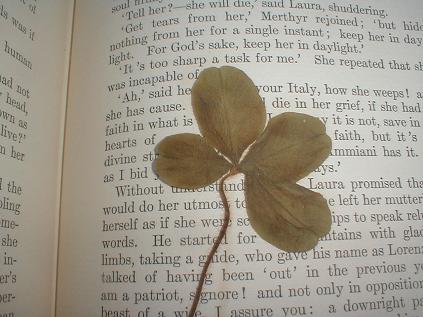

Publishing is not a game of chance where either you get lucky or you don't. That view is sometimes put forward by successful authors who wrap themselves in false humility in the hope that attributing their success to luck will save them from having to correspond with aspiring authors. While there are factors beyond any individual's control, like the timing of events or the rise and fall of fashions, it requires great dollops of either talent or industry to make a living as an author. I've noticed that some of the best writers put reading other authors at the top of their list of things you can do to improve your chances. Lately, I've been reading George Meridith, and the following picture is from the last volume of his multiple novel set on the Italian war for independence from the Hapsburg Empire.

I wonder is it's some Smith College thing I don't know about, like, by finding the four leaf clover I get to marry the student who put in in the book if I can locate her today. Of course, the book was last checked out in 1966, which means that student is close to collecting social security. I guess that would make me a gold digger:-)