I never used to get the point of HAM radio, a bunch of (mainly) guys hunched over radio sets trying to make contact with foreign radio operators and sending each other postcards for proof. But I started selling my ebooks internationally this summer with E-Junkie and PayPal, and I've been amazed at how fast the countries have stacked up. I've also been amazed to find that each new country I add feels like winning a prize. I finally broke down this week and created an alphabetized list (manually, so no surprise if I got the order wrong), which is up to 28 countries:

Argentina

Australia (15)

Austria

Belgium

Bermuda

Brazil (2)

Canada (4)

Chile

Cyprus

France

Honduras

Indonesia

Ireland (4)

Israel

Italy (2)

Japan

Mexico

Malaysia (2)

Micronesia

Netherlands (3)

New Zealand

Saudi Arabia

Spain

Sri Lanka

Switzerland

Taiwan

Trinidad and Tobago

United Kingdom (24)

English is the primary language in just three or four of these countries, so there are quite a few ESL (English as a second language) or expat Anglo ebook buyers living overseas. Aside from the strange satisfaction I get out of reaching people in so many countries so quickly, thanks to the Internet, there's potentially a grain of publishing knowledge in the data.

Why should Australia, with about a third of the population of the UK, account for two thirds as many sales as the UK? For some reason, Australians are about twice as likely to buy ebooks, or at least my ebooks, than UK residents. I can think of two possible reasons. First, if Australians live further from bookstores than people in the UK, there may be a natural tendency to buy ebooks online. Obviously the population density in Australia is much lower than the UK, but I don't know how it's distributed. If most Australians live in apartment blocks in large cities, it wouldn't be the case. Second, my books aren't easy to get in Australia without paying a lot for shipping and waiting a long time. The books are available in the UK through Amazon UK and several UK distributors.

Since I'm selling without DRM, I don't have to worry about international DRM issues. When Amazon first started selling ebooks supplied by Lightning Source back way back when, I would have sworn that they initially sold them internationally, then eventually cut back to US only. It may have had to to with customer support, local laws, or issues that generation of DRM software had with international platforms. Since my paper trail on those sales stopped at the distributor, I never knew where they were selling unless somebody dropped me a note.

I've been getting more correspondence and comments on the ebook selling subject lately, and I continue to be surprised by the dichotomy in the ebook publishing business. I don't doubt that new publishers following the various formulaic approaches to getting rich selling ebooks see it as being just as ethical than opening a new restaurant or clothing store. They do their market research and purchase advertising judiciously, then if the stars line up, they make a good profit. In a sense, putting the book last isn't that different from what the large trade publishers do, but there's something about selling people copy-written ebooks full of recycled Wikipedia content and Top Ten lists that bothers me as a business model. The best of those publishers are basically shooting for a finished ebook that doesn't leave the buyer feeling ripped-off. Aside from skirting the boundaries of ethical business practice, these publishers will never see any organic sales growth through word-of-mouth or free publicity. They'll always be locked into purchasing advertising from websites that have real content, and trying to make the dollars work out.

I do worry that shovelware ebooks give the whole ebook publishing business a bad name, and probably make international buyers extra wary of purchasing ebooks from a company they don't recognize. Maybe the fact that there are printed versions of my books for sale in bookstores gives some sophisticated overseas buyers the confidence to pay for the ebook version. It's the sort of thing I'd probably due a survey on if I were a corporation, but I hate getting "exit surveyed" after purchasing an item online myself, so I'm not going to force it on my own customers.

Print on Demand and ebook publishing have created a whole new model for publishing. Are POD and digital books the answer to an author's prayers, or just an evolutionary step between traditional publishing models and free Internet distribution?

Adsense

American Book Blight

Starting around 100 years ago, American Chestnut trees were infected by an imported blight which apparently originated in Japan or China. With no native resistance, the American Chestnuts, estimated at four billion strong, were wiped out. However, their root systems proved so resilient that they continue a shadowy existence under the canopy, throughout their native range. After sprouting from old roots, they out-compete the other young trees of the forest until they near maturity, when they contract the blight and die. Since they rarely mature sufficiently to flower and produce nuts, Darwinian mechanics has yet to produce a solution. While inspecting a property this morning near the Quabbin reservoir Massachusetts, I came upon a whole grove of young American Chestnuts, distinguishable primarily by their leaves:

One of the trees in the grove was surprisingly mature, I'd estimate the diameter nearly six inches, though you can see the blight cankers stretching vertically on the bark.

American Book Blight came along much later than the Chestnut Blight, and there's no blaming foreigners for this one. I'd suggest American Book Blight took off in the 1970's, grew steadily until the early 1990's, and then took a huge jump as book superstores, discount chains and Amazon changed the economics of the book business. Instead of tens of thousands of new titles reaching maturity each year from a hundred thousand seedlings, only a few thousand titles grow to maturity these days. The sales of those mature titles have become super-sized, with bestsellers routinely going over a million copies, but what's lacking are the tens of thousands of new mid-list or back-list titles selling in commercial quantities. Trade publishing is more of a lottery, winner-take-all game than it was a few decades ago, though part of this may be due to the decreasing influence of the library market.

My first solution for the American book blight was given in my last post about trade publishing lay-offs. A new crop of publishers is what it will take to nurture and grow the next generation of blight resistant titles to a modest maturity. Large trades can't make a profit planning new titles that will sell on the order of a thousand copies a year, but a long-lived grove of such titles will keep a self publisher in nuts for the cold winters ahead. New independent publishers who adopt print-on-demand economics may need to sell a several times that number unless they charge astronomical cover prices, but a modest list averaging three or four thousand units per title per year can pay a couple salaries.

Scientists have been working for years to breed a blight resistant American Chestnut hybrid, hoping that a tree that is 15/16ths American (and 1/16th Chinese) may prove blight resistant enough to repopulate the East Coast range. I think a similar hybrid approach is key to beating American Book Blight, but I'd suggest more than a 16th of non-paper revenues in the mix. I'm currently trying to move my own publishing business to a 50/50 model, 50% paper books printed on demand and 50% electronic, from Ebooks or web revenue. If I can get there, it will be a model that allows even smaller market books to mature, flower and provide the publisher with enough nuts to last year-round. And remember, if you ever get into a conversation with a forestry type who gets on the subject of the chestnut blight, and you want to make a bad impression, interrupt with , "Oh yes, American Chestnuts. Them's good burning"

One of the trees in the grove was surprisingly mature, I'd estimate the diameter nearly six inches, though you can see the blight cankers stretching vertically on the bark.

American Book Blight came along much later than the Chestnut Blight, and there's no blaming foreigners for this one. I'd suggest American Book Blight took off in the 1970's, grew steadily until the early 1990's, and then took a huge jump as book superstores, discount chains and Amazon changed the economics of the book business. Instead of tens of thousands of new titles reaching maturity each year from a hundred thousand seedlings, only a few thousand titles grow to maturity these days. The sales of those mature titles have become super-sized, with bestsellers routinely going over a million copies, but what's lacking are the tens of thousands of new mid-list or back-list titles selling in commercial quantities. Trade publishing is more of a lottery, winner-take-all game than it was a few decades ago, though part of this may be due to the decreasing influence of the library market.

My first solution for the American book blight was given in my last post about trade publishing lay-offs. A new crop of publishers is what it will take to nurture and grow the next generation of blight resistant titles to a modest maturity. Large trades can't make a profit planning new titles that will sell on the order of a thousand copies a year, but a long-lived grove of such titles will keep a self publisher in nuts for the cold winters ahead. New independent publishers who adopt print-on-demand economics may need to sell a several times that number unless they charge astronomical cover prices, but a modest list averaging three or four thousand units per title per year can pay a couple salaries.

Scientists have been working for years to breed a blight resistant American Chestnut hybrid, hoping that a tree that is 15/16ths American (and 1/16th Chinese) may prove blight resistant enough to repopulate the East Coast range. I think a similar hybrid approach is key to beating American Book Blight, but I'd suggest more than a 16th of non-paper revenues in the mix. I'm currently trying to move my own publishing business to a 50/50 model, 50% paper books printed on demand and 50% electronic, from Ebooks or web revenue. If I can get there, it will be a model that allows even smaller market books to mature, flower and provide the publisher with enough nuts to last year-round. And remember, if you ever get into a conversation with a forestry type who gets on the subject of the chestnut blight, and you want to make a bad impression, interrupt with , "Oh yes, American Chestnuts. Them's good burning"

Downsized and Laid-off Publishing Employee Retraining

So you've been working at publisher X for the last ten years and the axe just fell. They're sorry to have to let you go, but your job has been made redundant through mergers and downsizing. The number of titles is growing but the bookstore business is stagnant and anybody who keeps a job at a large trade in the future will really be working for Amazon. Well, here's your chance to leave the dark side and join forces with the children of the light working in independent and self publishing.

I've known some really competent people who worked for trade publishers and I've known some real clowns, but one thing stands out. You can develop valuable job skills during a career in trade publishing, but unfortunately, most of them are essentially corporate get-along skills. Out here in the non-corporate world, dressing to impress, yessing to say "yes", making a great pot of coffee and giving good meetings are non-marketable skills. Wait, I take it back about the coffee. Mastery of spreadsheets can only get you in trouble and a fine appreciation of "the right way to do things" means you're a dinosaur, and not one of the scary ones.

But if you've watched your laid-off editor friends drop out of the industry one-by-one as they bang up against the invisible age ceiling, or if you're tired of going home to live with your parents every few years, it's time to get off the trade publishing merry-go-round. While I'm fond of pointing out to new authors and publishers that it's a tough business, that's where you have an advantage coming from the trade world. You already know that publishing is a business where only the strong make money, and you probably know quite a bit about market research. Let's face it, trade publishers excel at market research, if they were also good at acquiring and producing and marketing books that met that demand, you wouldn't be looking for a job right now.

As part of my outreach program to former developmental and acquisitions editors, I want to stress two points. First, you can't plan to replicate the business model that you're used to, but on a smaller scale. It's employees that are easy to downsize, not business models. You've rewritten or finished enough books for deadbeat authors, it's time to write one yourself. The great thing about being laid-off in America (so I hear) is collecting unemployment, so don't waste the chance by sitting on the couch and watching TV, or by blowing the money playing at being in business. Launch your publishing website today, and figure it out as you go along. Nobody is looking over your shoulder anymore, you can mess up all you want. But it's time to get out of corporate gear and shift up to self-employed gear, and if you can do it without coffee, you'll live longer.

I've known some really competent people who worked for trade publishers and I've known some real clowns, but one thing stands out. You can develop valuable job skills during a career in trade publishing, but unfortunately, most of them are essentially corporate get-along skills. Out here in the non-corporate world, dressing to impress, yessing to say "yes", making a great pot of coffee and giving good meetings are non-marketable skills. Wait, I take it back about the coffee. Mastery of spreadsheets can only get you in trouble and a fine appreciation of "the right way to do things" means you're a dinosaur, and not one of the scary ones.

But if you've watched your laid-off editor friends drop out of the industry one-by-one as they bang up against the invisible age ceiling, or if you're tired of going home to live with your parents every few years, it's time to get off the trade publishing merry-go-round. While I'm fond of pointing out to new authors and publishers that it's a tough business, that's where you have an advantage coming from the trade world. You already know that publishing is a business where only the strong make money, and you probably know quite a bit about market research. Let's face it, trade publishers excel at market research, if they were also good at acquiring and producing and marketing books that met that demand, you wouldn't be looking for a job right now.

As part of my outreach program to former developmental and acquisitions editors, I want to stress two points. First, you can't plan to replicate the business model that you're used to, but on a smaller scale. It's employees that are easy to downsize, not business models. You've rewritten or finished enough books for deadbeat authors, it's time to write one yourself. The great thing about being laid-off in America (so I hear) is collecting unemployment, so don't waste the chance by sitting on the couch and watching TV, or by blowing the money playing at being in business. Launch your publishing website today, and figure it out as you go along. Nobody is looking over your shoulder anymore, you can mess up all you want. But it's time to get out of corporate gear and shift up to self-employed gear, and if you can do it without coffee, you'll live longer.

Revised Thoughts on Book Editions and Revisions

The received wisdom for most publishers using print-on-demand and selling primarily through the Internet is “never release a new edition.” It’s sort of funny, considering the low inventory aspect of POD allows for edition changes without creating a remainder headache, but the reason is brutally commercial. A new edition traditionally means a new ISBN number, and a new ISBN number means a new product page and sales history on Amazon. Publishers who focus all of their efforts on the Amazon platform (and those who simply end up selling most of their books through Amazon by default) risk losing their position in Amazon search and recommendation lists, along with accumulated reviews if the transfer isn’t seamless. The result may leave the publisher starting out from scratch all over again.

In some instances, such as college textbooks, new editions are simply a sleazy way to force students to abandon the old textbook, preventing them from purchasing used books, or accepting hand-me-downs. But many nonfiction books, especially reference works and successful how-to titles, go through regular editions as technology or conditions change. Yes, a well written book on preparing your Federal Income Taxes from 2001 would still be useful today, but not as useful as a well written one updated for 2008. A cookbook may live for decades without requiring a rewrite, but a restaurant guide may get revised every year. Most nonfiction titles fall between the extremes of “good for decades” vs “requires annual update”. The issue faced by POD publishers updating a book is balancing the visibility of the current ISBN vs customer confusion over what they are buying, especially when used books with a different interior are being sold alongside the new ones.

Earlier this summer, I updated the contents of my publishing book without releasing a revised edition. I felt comfortable doing this for a few reasons, but primarily because the book required little updating and most of those updates amounted to deleting descriptions of Amazon functions that are no longer in force. Until today, I don’t think I even mentioned on my own site that the book had been updated, though maybe I’ll add a note to my sales page. I’m comfortable that there can’t be many copies of the old version floating around for sale as new, because Ingram has cycled through their entire stock of the book twice since I revised it and Amazon doesn’t physically stock it. I simply didn’t make enough changes to the book to declare a new or revised edition.

In couple of weeks, I’ll be releasing a revised edition of one of my computer books, which I’ll publish with a new ISBN number and identify as a revised edition in the title and in the book information. I also intend to add a note to the annotation discouraging buyers of the original edition from buying the revised edition. In this case, while the revisions took quite a bit of work, they don’t bring any fundamental new knowledge to the reader, they simply deal with some newer technologies. But as a computer technology title, I do want potential buyers to know that the book has been updated since it was first released five years ago, a long time for a technology title. The reason I went with “revised edition” rather than “second edition” is because I think there’s less chance that buyers of the original edition will confuse it with a major rewrite.

Once I release the new edition, I’ll change my returns policy on the old edition and give stores at least three months to sell the old copies or return them. Maybe I’ll take the book officially out of print before New Years, but I’m curious to see what happens in the marketplace and on Amazon and will certainly report on it. Since my website drives the majority of the sales for my books, I’m not particularly worried about loss of place on Amazon, and the computer hardware book genre is rapidly dying off in any case. In an interesting twist, I think I’m in a decent position to be one of the last publishers standing in the field, since sales really don’t justify any new titles being produced. Just a couple of us issuing the occasional revision to an ever shrinking audience, but dealing with less competition as well.

In some instances, such as college textbooks, new editions are simply a sleazy way to force students to abandon the old textbook, preventing them from purchasing used books, or accepting hand-me-downs. But many nonfiction books, especially reference works and successful how-to titles, go through regular editions as technology or conditions change. Yes, a well written book on preparing your Federal Income Taxes from 2001 would still be useful today, but not as useful as a well written one updated for 2008. A cookbook may live for decades without requiring a rewrite, but a restaurant guide may get revised every year. Most nonfiction titles fall between the extremes of “good for decades” vs “requires annual update”. The issue faced by POD publishers updating a book is balancing the visibility of the current ISBN vs customer confusion over what they are buying, especially when used books with a different interior are being sold alongside the new ones.

Earlier this summer, I updated the contents of my publishing book without releasing a revised edition. I felt comfortable doing this for a few reasons, but primarily because the book required little updating and most of those updates amounted to deleting descriptions of Amazon functions that are no longer in force. Until today, I don’t think I even mentioned on my own site that the book had been updated, though maybe I’ll add a note to my sales page. I’m comfortable that there can’t be many copies of the old version floating around for sale as new, because Ingram has cycled through their entire stock of the book twice since I revised it and Amazon doesn’t physically stock it. I simply didn’t make enough changes to the book to declare a new or revised edition.

In couple of weeks, I’ll be releasing a revised edition of one of my computer books, which I’ll publish with a new ISBN number and identify as a revised edition in the title and in the book information. I also intend to add a note to the annotation discouraging buyers of the original edition from buying the revised edition. In this case, while the revisions took quite a bit of work, they don’t bring any fundamental new knowledge to the reader, they simply deal with some newer technologies. But as a computer technology title, I do want potential buyers to know that the book has been updated since it was first released five years ago, a long time for a technology title. The reason I went with “revised edition” rather than “second edition” is because I think there’s less chance that buyers of the original edition will confuse it with a major rewrite.

Once I release the new edition, I’ll change my returns policy on the old edition and give stores at least three months to sell the old copies or return them. Maybe I’ll take the book officially out of print before New Years, but I’m curious to see what happens in the marketplace and on Amazon and will certainly report on it. Since my website drives the majority of the sales for my books, I’m not particularly worried about loss of place on Amazon, and the computer hardware book genre is rapidly dying off in any case. In an interesting twist, I think I’m in a decent position to be one of the last publishers standing in the field, since sales really don’t justify any new titles being produced. Just a couple of us issuing the occasional revision to an ever shrinking audience, but dealing with less competition as well.

Formatting Tables And Kindle Business Model

I've been getting fairly regular questions about publishing on Kindle so I finally decided to go ahead and publish my own Kindle ebook, just to be in a better position to respond. It turned out to be far more work than I'd hoped for a mediocre result, and a bit frustrating as well since the Amazon previewer doesn't test whether or not table of contents links are working. I asked a fellow publisher, Kim Greenblatt, to check it out for me since he owns a Kindle. That he needed to "dig it out" and charge it up suggests that it hasn't become is primary reading device:-)

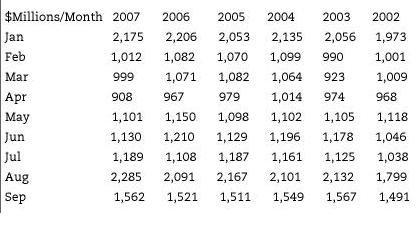

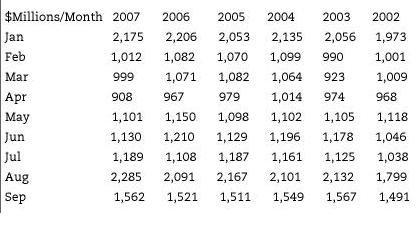

The biggest problem I ran into was formatting tables. The reason it's a problem is that Kindle doesn't support HTML table tags. Since HTML doesn't support tabs or repeated spaces, my "fix" was to use underscore characters "_" and periods "." to try to line up the data, and then set the color to white. On the smaller tables it's not horrible with the default font, on the larger tables, the columns get pretty squiggly. There's also the issue with page breaks in the middle of tables, but rather than force page breaks for every table, I decided to repeat the column labels in the bottom row. The picture below is from the preview tool which apparently is a fair representation of the Kindle screen, from a large table that came out OK.

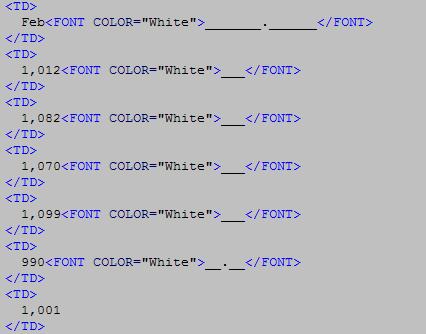

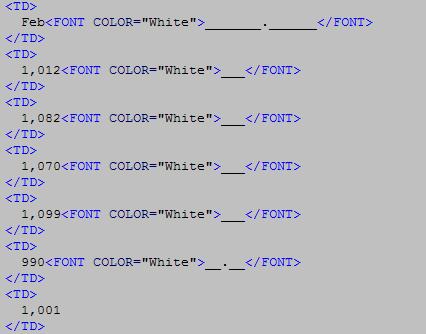

A glimpse of HTML to accomplish this:

The reason I left table tags in there was so that I would have some way of aligning the columns in my HTML editor as I was working. It would be funny if Kindle started recognizing HTML table formatting one day, and all of a sudden my tables got even screwier. The other main formatting notes for Kindle are that you have to put in an HTML anchor for the Table of Contents itself, in addition for the links and anchors to all of the chapters, if you want a clickable TOC. There's a guy who's started a Kindle formatting site where I found the name of the pagebreak tag, "mbp:pagebreak /" (goes inside less-than greater-than signs like all HTML tags) which given the "mbp" was probably developed for MobiPocket.

One of the reasons I didn't bother publishing any books on Kindle when it came out is the business model. The contract Amazon requires publishers to sign for Kindle is pretty out-there. I wouldn't have signed if not for the clause allowing either party to opt out on 60 days notice, though I probably should have checked with my lawyer as well. The royalty to the publisher is 35%, which means, of the five ways I sell my publishing title, I earn the least on the Kindle version by a factor of at least two. I set the list price at $9.95, the same price for which I sell my PDF e-book version direct. Amazon discounts the $9.95 Kindle version by 20%, so they are now the cheapest way somebody can legally acquire an ebook version of my publishing book, though you do have to pop $359 for a Kindle to save the two dollars. Since I earn around $7.50 per copy on the paperback sold through Amazon, each Kindle sale to somebody who would have bought the paperback otherwise will cut my net in half. For the time being, I don't think it will break my bank.

While it would be nice to earn a higher share as the publisher, I assume that Amazon is paying a hefty fee to the cellular operators who host their Whispernet, and for all I know they'll lose more than I make on every copy they sell. But I see Kindle as part of Amazon's grand plan to compel publishers to supply Amazon with electronic files for all their titles for Amazon to package and sell as they see fit. I'm not on-board with that future, but I decided to go ahead with this one Kindle version just to learn what it's all about. If anybody is interested in how Kindle e-books are selling, see the comments from Steve Windwalker on my earlier ramblings about Kindle sales ranks.

A side note, I just noticed that Google has me at #1 for searches on Publisher TV, so I think that justifies my summer of video reruns!

The biggest problem I ran into was formatting tables. The reason it's a problem is that Kindle doesn't support HTML table tags. Since HTML doesn't support tabs or repeated spaces, my "fix" was to use underscore characters "_" and periods "." to try to line up the data, and then set the color to white. On the smaller tables it's not horrible with the default font, on the larger tables, the columns get pretty squiggly. There's also the issue with page breaks in the middle of tables, but rather than force page breaks for every table, I decided to repeat the column labels in the bottom row. The picture below is from the preview tool which apparently is a fair representation of the Kindle screen, from a large table that came out OK.

A glimpse of HTML to accomplish this:

The reason I left table tags in there was so that I would have some way of aligning the columns in my HTML editor as I was working. It would be funny if Kindle started recognizing HTML table formatting one day, and all of a sudden my tables got even screwier. The other main formatting notes for Kindle are that you have to put in an HTML anchor for the Table of Contents itself, in addition for the links and anchors to all of the chapters, if you want a clickable TOC. There's a guy who's started a Kindle formatting site where I found the name of the pagebreak tag, "mbp:pagebreak /" (goes inside less-than greater-than signs like all HTML tags) which given the "mbp" was probably developed for MobiPocket.

One of the reasons I didn't bother publishing any books on Kindle when it came out is the business model. The contract Amazon requires publishers to sign for Kindle is pretty out-there. I wouldn't have signed if not for the clause allowing either party to opt out on 60 days notice, though I probably should have checked with my lawyer as well. The royalty to the publisher is 35%, which means, of the five ways I sell my publishing title, I earn the least on the Kindle version by a factor of at least two. I set the list price at $9.95, the same price for which I sell my PDF e-book version direct. Amazon discounts the $9.95 Kindle version by 20%, so they are now the cheapest way somebody can legally acquire an ebook version of my publishing book, though you do have to pop $359 for a Kindle to save the two dollars. Since I earn around $7.50 per copy on the paperback sold through Amazon, each Kindle sale to somebody who would have bought the paperback otherwise will cut my net in half. For the time being, I don't think it will break my bank.

While it would be nice to earn a higher share as the publisher, I assume that Amazon is paying a hefty fee to the cellular operators who host their Whispernet, and for all I know they'll lose more than I make on every copy they sell. But I see Kindle as part of Amazon's grand plan to compel publishers to supply Amazon with electronic files for all their titles for Amazon to package and sell as they see fit. I'm not on-board with that future, but I decided to go ahead with this one Kindle version just to learn what it's all about. If anybody is interested in how Kindle e-books are selling, see the comments from Steve Windwalker on my earlier ramblings about Kindle sales ranks.

A side note, I just noticed that Google has me at #1 for searches on Publisher TV, so I think that justifies my summer of video reruns!

Alternative Career Options For Self Publishers

I got poked in the eye by a wire while doing some construction work a few days ago, sprung right past my glasses and got me. Since it was my "good" eye, the one that compensates for the defect in the other eye, it left me seeing double for a day and unable to read. That got me thinking about what I'd be doing if I couldn't continue as a self publisher. I know there's a lot of new whiz-bang reader technology out there that might help compensate for the inability to read books or newspapers, but I can't imagine doing heavy Internet work with all the skim reading and scrolling without the ability to read easily.

And that got me thinking about career options for self publishers in general. I know a few self publishers who have moved on to work for large trades, but the normal career path is the opposite, with trade authors fleeing into self publishing. Many self employed people, regardless of the industry, find themselves becoming "unemployable" with the passing of time. It's not just that our skill become aligned with self employment goals, it's also that our personalities develop, shall we say, eccentricities. I have to admit that my general reaction on hearing workplace complaints from friends and strangers alike is, "Why don't you quit?" But quitting twice a week is a tough way to develop a career.

If I couldn't make a living publishing anymore, either through some physical impairment or a loss of creativity, I suppose I'd try to limp by as a consultant for a while. Telling other people how to do things you can't do yourself is a common exit strategy for many a fallen expert, and unexpectedly, a common entry strategy for not a few publishing "experts" who've never published a successful book. But consulting is a pretty tough ABC (Always Be Closing) career and I don't think I'd enjoy it at all. There was a time that I might have thought about opening a used book store, but Amazon has done a pretty good job putting limits on that particular career path.

That I would stay self employed is a given. I haven't considered myself to be employable for the last fifteen years, but I'm flexible as to the work and the pay. The problem is, most of the ideas I come up with have to do with me doing something I enjoy rather than with making a living. That's where I've been lucky with self publishing, since I enjoy it most of the time and still make a living at it. Now I know what you're thinking, that I could get rich dictating novels and screenplays to an assistant by the pool, probably an attractive Ivy league girl who abandons her education for a chance to work with me. But somehow I just don't see it in the cards, and if you do, I'd recommend putting off the morning drink at least to after supper:-)

And that got me thinking about career options for self publishers in general. I know a few self publishers who have moved on to work for large trades, but the normal career path is the opposite, with trade authors fleeing into self publishing. Many self employed people, regardless of the industry, find themselves becoming "unemployable" with the passing of time. It's not just that our skill become aligned with self employment goals, it's also that our personalities develop, shall we say, eccentricities. I have to admit that my general reaction on hearing workplace complaints from friends and strangers alike is, "Why don't you quit?" But quitting twice a week is a tough way to develop a career.

If I couldn't make a living publishing anymore, either through some physical impairment or a loss of creativity, I suppose I'd try to limp by as a consultant for a while. Telling other people how to do things you can't do yourself is a common exit strategy for many a fallen expert, and unexpectedly, a common entry strategy for not a few publishing "experts" who've never published a successful book. But consulting is a pretty tough ABC (Always Be Closing) career and I don't think I'd enjoy it at all. There was a time that I might have thought about opening a used book store, but Amazon has done a pretty good job putting limits on that particular career path.

That I would stay self employed is a given. I haven't considered myself to be employable for the last fifteen years, but I'm flexible as to the work and the pay. The problem is, most of the ideas I come up with have to do with me doing something I enjoy rather than with making a living. That's where I've been lucky with self publishing, since I enjoy it most of the time and still make a living at it. Now I know what you're thinking, that I could get rich dictating novels and screenplays to an assistant by the pool, probably an attractive Ivy league girl who abandons her education for a chance to work with me. But somehow I just don't see it in the cards, and if you do, I'd recommend putting off the morning drink at least to after supper:-)

Sell Me Your Copyrights, Publishing Business, Website

I'm officially back in the market for publishing business assets as of today. It's part of a two pronged plan to grow my publishing business through acquisition and to create a new marketplace for orphaned intellectual property. I also think it would be a lot more useful (and fun) way to spend my time for the rest of the year than running a fiction contest for self published writers.

The idea of aggregating the micro assets of authors and publishers who have either exited the business or exited this life has been tugging at my brain for years. I think it originally came to mind when I was doing some estate planning, and the idea became fixed last summer when I did a study of small publishers who went out of business and abandoned their websites.

The basic premise, in a nutshell, is that a tremendous amount of intellectual property built up in books and websites must simply dissipate into nothingness every year. People either give up on business and don't have a ready market, or owners pass on and estate executors either don't recognize the value or don't have any way to realize it. With the Internet and print-on-demand, fairly small grains of intellectual property can be added up to make a worthwhile business, provided there's a practical way to find and acquire the copyrights. Ten years ago, I don't know what you'd have done with a publishing business that only sold a couple hundred books a year, but as long as those titles have lasting value, it now makes sense for another publisher to keep them in print, and perhaps get them online.

Since I've blogged about this stuff for a couple years, I already rank at the top of Google for many phrases related to buying or selling a publishing asset. But most of the people who contact me have insanely unrealistic expectations. They think their businesses should be valued by the investment they put in, which can run six figures, rather than by the sales, which can run four figures for the same. I think the reason I never hear from the sort of people with the small niche assets I was talking about above is that they don't think selling those assets is practical. They just wind down operations, pay their bills, and put the leftover books in the attic and let the website registration expire.

For the time being, the next step is advertising, and I'll start with an Adwords campaign to test the waters before rushing into print advertising in the various publishing newsletters or magazines. I wonder if there's an organization of estate liquidation attorneys where I could advertise? In the meantime, I'm willing to talk to anybody who has ideas on the subject, so don't hesitate to comment on this post or get in touch by e-mail. I'm hoping that at some point I can build a directory or resource that would become well known, so that people with copyrights and intellectual property assets they figured wouldn't be worth the bother of trying to sell will list them. The original owners would get the benefit of the selling price and seeing the work remain in print, or even get updated, while the buyer have a new path for expanding a small publishing business.

And please feel free to link to this post from any publishing discussion group you may participate in. The more feedback I get now, the more likely I am to invest significant money in building a new website rather than trying to limp along with a one page directory on this site.

The idea of aggregating the micro assets of authors and publishers who have either exited the business or exited this life has been tugging at my brain for years. I think it originally came to mind when I was doing some estate planning, and the idea became fixed last summer when I did a study of small publishers who went out of business and abandoned their websites.

The basic premise, in a nutshell, is that a tremendous amount of intellectual property built up in books and websites must simply dissipate into nothingness every year. People either give up on business and don't have a ready market, or owners pass on and estate executors either don't recognize the value or don't have any way to realize it. With the Internet and print-on-demand, fairly small grains of intellectual property can be added up to make a worthwhile business, provided there's a practical way to find and acquire the copyrights. Ten years ago, I don't know what you'd have done with a publishing business that only sold a couple hundred books a year, but as long as those titles have lasting value, it now makes sense for another publisher to keep them in print, and perhaps get them online.

Since I've blogged about this stuff for a couple years, I already rank at the top of Google for many phrases related to buying or selling a publishing asset. But most of the people who contact me have insanely unrealistic expectations. They think their businesses should be valued by the investment they put in, which can run six figures, rather than by the sales, which can run four figures for the same. I think the reason I never hear from the sort of people with the small niche assets I was talking about above is that they don't think selling those assets is practical. They just wind down operations, pay their bills, and put the leftover books in the attic and let the website registration expire.

For the time being, the next step is advertising, and I'll start with an Adwords campaign to test the waters before rushing into print advertising in the various publishing newsletters or magazines. I wonder if there's an organization of estate liquidation attorneys where I could advertise? In the meantime, I'm willing to talk to anybody who has ideas on the subject, so don't hesitate to comment on this post or get in touch by e-mail. I'm hoping that at some point I can build a directory or resource that would become well known, so that people with copyrights and intellectual property assets they figured wouldn't be worth the bother of trying to sell will list them. The original owners would get the benefit of the selling price and seeing the work remain in print, or even get updated, while the buyer have a new path for expanding a small publishing business.

And please feel free to link to this post from any publishing discussion group you may participate in. The more feedback I get now, the more likely I am to invest significant money in building a new website rather than trying to limp along with a one page directory on this site.

Statistics on Self Employed Authors And Writers

Does relative scarcity translate into value? Not always, as self employed writers can tell you. Dozens of the books are published every year on the subject of selling articles and manuscripts. If we include books on writing effectively, promoting your work, or preparing screenplays, the number of how-to guides published each year may be in the hundreds. But the employment statistics for writers tell a different story.

The 2007 census numbers estimate that just over 44,000 people nationwide are professional writers or authors, and that includes people who make their primary living in other professions. There are more technical writers, at 47,000, then mainstream writers, and tellingly, there are more editors at 105,000 than writers of both ilks combined. That suggests that a lot of editors are either composing their own copy from press releases, wire services and other sources, or employing large numbers of part-time stringers who aren't counted in the writer totals. Of course, as nobody sent me the survey I have my doubts about the accuracy:-)

So, I decided to try the REAL statistics guys, and after a while of digging around the IRS website, found the spreadsheet for Schedule C reporting for 2005 (the last tax year available) by business type. Note that this isn't the 711510 code for independent writers, artists, etc., it's 511110 code for Publishing Industries (except internet). Just under 92,000 business tax returns for sole proprietorships were filed as publishing businesses, which excludes giant corporations, LLC's, etc. The total net income of publishing businesses reporting a profit for 2005 was $942 million. Around a quarter of filers, 21,000 in all, reported a loss. The average sales of the profitable group was $27,000. The average sales of the unprofitable group was $14,000.

Looking at the profitable publishers only, the average net income for the entire publishing group was just $13,348 per business! It's also interesting to note that the $942 million in net income was on about $2.47 billion in sales, so margins are pretty good for publishers who have sales. The reported payroll for profitable sole proprietors filing as publishers was $200 million in 2005, meaning if every business had a single employee, the average salary would be about $2,800 a year, but of course, most self publishers and not a few micro-presses have no employees, so the average is higher. Not surprisingly, the average payroll at the unprofitable publishers was much higher at around $4,700.

So the average self publishing author who reports income as a publishing business is earning less than $10,000/year in net profit. In some cases, those publishers are simply smarter than me about generating more expenses so they have less net income. But on the whole, I suspect the equation looks more like

limited sales = limited gross income = limited net profit

But on the whole, the tax numbers offer a more encouraging picture than the labor statistics numbers, even though all sole proprietorships filing as publishers aren't self employed authors or writers. In fact, many self publishers probably file as 711510 code writers, but that's what makes statistics fun.

The 2007 census numbers estimate that just over 44,000 people nationwide are professional writers or authors, and that includes people who make their primary living in other professions. There are more technical writers, at 47,000, then mainstream writers, and tellingly, there are more editors at 105,000 than writers of both ilks combined. That suggests that a lot of editors are either composing their own copy from press releases, wire services and other sources, or employing large numbers of part-time stringers who aren't counted in the writer totals. Of course, as nobody sent me the survey I have my doubts about the accuracy:-)

So, I decided to try the REAL statistics guys, and after a while of digging around the IRS website, found the spreadsheet for Schedule C reporting for 2005 (the last tax year available) by business type. Note that this isn't the 711510 code for independent writers, artists, etc., it's 511110 code for Publishing Industries (except internet). Just under 92,000 business tax returns for sole proprietorships were filed as publishing businesses, which excludes giant corporations, LLC's, etc. The total net income of publishing businesses reporting a profit for 2005 was $942 million. Around a quarter of filers, 21,000 in all, reported a loss. The average sales of the profitable group was $27,000. The average sales of the unprofitable group was $14,000.

Looking at the profitable publishers only, the average net income for the entire publishing group was just $13,348 per business! It's also interesting to note that the $942 million in net income was on about $2.47 billion in sales, so margins are pretty good for publishers who have sales. The reported payroll for profitable sole proprietors filing as publishers was $200 million in 2005, meaning if every business had a single employee, the average salary would be about $2,800 a year, but of course, most self publishers and not a few micro-presses have no employees, so the average is higher. Not surprisingly, the average payroll at the unprofitable publishers was much higher at around $4,700.

So the average self publishing author who reports income as a publishing business is earning less than $10,000/year in net profit. In some cases, those publishers are simply smarter than me about generating more expenses so they have less net income. But on the whole, I suspect the equation looks more like

limited sales = limited gross income = limited net profit

But on the whole, the tax numbers offer a more encouraging picture than the labor statistics numbers, even though all sole proprietorships filing as publishers aren't self employed authors or writers. In fact, many self publishers probably file as 711510 code writers, but that's what makes statistics fun.

My Internet Publishing Expert Hat

A couple comments for a lazy Thursday about my "position" as a self publishing expert. In case you're wondering who voted me into the position, it has something to do with this blog, my publishing book and the video channel. It also has to do with the lack of competition for an unpaid position answering questions and keeping up with the publishing industry news, especially as pertains to book sales and markets.

On the advice of Jon Reed, the moderator of the POD Publishers group, I changed the comment settings on my blog this week to allow comments from anybody. The caveat is that I still moderate all comments, and I automatically reject comments on posts more than a couple months old. My main goal in comment moderation, aside from eliminating spam, is making sure that the comments have something to do with the posts.

If you want to ask me a question and you can't find a recent post related to the topic, just e-mail me direct. But please don't waste my time or yours with questions like, "How do I publish a book?" or "Will you publish my memoir?". The whole point of going to an expert for help is to ask specific, informed questions, and if you can stump the expert, it's a good sign. I love it when people ask questions that teach me something new.

Keep in mind also that I'm in the market for publishing assets, both websites and existing lists, but that's strictly business. I've heard from several publishers in the past looking to sell their title lists who have never made any money. Let me ask a question for a change. Why in the world would anybody want to pay a publisher to take over a list of titles that don't sell? The same goes for websites that don't get any visitors. The amount of money which you've invested in building something you think of as an asset is irrelevant. If it doesn't generate revenue, it's not an asset, it's an expense, and you'd have to pay somebody to take it off your hands. I'd much rather start buying Espresso POD machines and trying set up a leasing business:-)

Finally, despite the protective headgear I wear in a couple videos, I'm not a mind reader. If you check my blog twice a week in hopes that I'll write about some topic that I never get around to, drop me a line and let me know. But keep in mind that I'm not a "feel good" guy, I'm not interested in blogging about how you can work out your personal issues by writing a memoir or the like. As my readers occasionally remind me, this blog is supposed to be about the publishing business, which means, making money. If you aren't making money publishing, it's not a business, it's a hobby, and the IRS can fill you in on the details.

On the advice of Jon Reed, the moderator of the POD Publishers group, I changed the comment settings on my blog this week to allow comments from anybody. The caveat is that I still moderate all comments, and I automatically reject comments on posts more than a couple months old. My main goal in comment moderation, aside from eliminating spam, is making sure that the comments have something to do with the posts.

If you want to ask me a question and you can't find a recent post related to the topic, just e-mail me direct. But please don't waste my time or yours with questions like, "How do I publish a book?" or "Will you publish my memoir?". The whole point of going to an expert for help is to ask specific, informed questions, and if you can stump the expert, it's a good sign. I love it when people ask questions that teach me something new.

Keep in mind also that I'm in the market for publishing assets, both websites and existing lists, but that's strictly business. I've heard from several publishers in the past looking to sell their title lists who have never made any money. Let me ask a question for a change. Why in the world would anybody want to pay a publisher to take over a list of titles that don't sell? The same goes for websites that don't get any visitors. The amount of money which you've invested in building something you think of as an asset is irrelevant. If it doesn't generate revenue, it's not an asset, it's an expense, and you'd have to pay somebody to take it off your hands. I'd much rather start buying Espresso POD machines and trying set up a leasing business:-)

Finally, despite the protective headgear I wear in a couple videos, I'm not a mind reader. If you check my blog twice a week in hopes that I'll write about some topic that I never get around to, drop me a line and let me know. But keep in mind that I'm not a "feel good" guy, I'm not interested in blogging about how you can work out your personal issues by writing a memoir or the like. As my readers occasionally remind me, this blog is supposed to be about the publishing business, which means, making money. If you aren't making money publishing, it's not a business, it's a hobby, and the IRS can fill you in on the details.